Farmington, MA: Alice James Books, 2012. 78 pages. $15.95.

The world continues to remember Nina Simone (formerly Eunice Kathleen Waymon) as a storyteller through songs, whose body of work created a legacy of compassion, empowerment and liberation. At the time of Simone’s death on April 21, 2003, she was already among the 20th century’s most extraordinary artists.

But, to poet Monica Hand, this song griot was something else. Reading Hand’s poems, it’s clear that Nina Simone is the center around which a carousel of memories revolves in Hand’s new collection of poems me and Nina (Alice James Books, 2012). And I have to agree with poet Terrance Hayes calling this book “a debut fiercely illuminated by declaration and song.”

Those declaration songs aren’t overshadowed by Nina Simone’s presence. Instead, Hand masterfully weaves Simone’s bio throughout her own. We get glimpses of Simone in the poem “X is for Xenophobia”:

like the x

in a geometry problem or hex

I don’t understand their pain

why they act like chickens in a pen

as if they felt at their nap

broken bone

why they want me alone hobo

for preaching hope

for reminding people we are Ibo

not bane

cause of soullessness they took an ax

to my happiness I want to open

the door play classical piano

now my hipbone

slips to Obeah

I am the unanswered z y x

Hand’s speaker in “X” might be alluding to Simone’s critics unable to file her musical style. “Critics started to talk about what sort of music I was playing, and tried to find a neat slot to file it away in,” Simone wrote in her 1991 autobiography I Put A Spell On You. “It was difficult for them because I was playing popular songs in a classical style with a classical piano technique influenced by cocktail jazz.

“On top of that I included spirituals and children’s song in my performances, and those sorts of songs were automatically identified with the folk movement. So, saying what sort of music I played gave the critics problems because there was something from everything in there, but it also meant I was appreciated across the board – by jazz, folk, pop and blues fans as well as admirers of classical music.”

The one thing Nina Simone struggled with musically was mixing politics with popular music. “That was the musical side of it I shied away from,” according to her autobiography. “I didn’t like ‘protest music’ because a lot of it was so simple and unimaginative it stripped the dignity away from people it was trying to celebrate.”

That was until “Mississippi Goddam,” Simone’s tribute to Civil Rights activist Medgar Evers and the four girls killed in the Alabama church bombing. The South banned Simone’s song and performances.

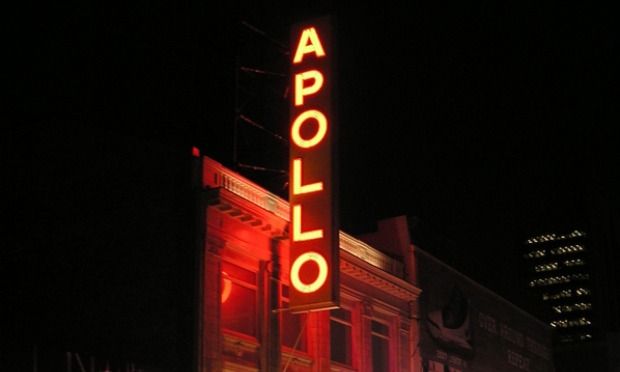

Hand’s speaker brings us from the South to New York City to see Nina Simone perform that song at the Apollo Theater in the poem “Black is Beautiful”. That night, Hand’s speaker and her friend “D” are rocking their “crushed-velvet jackets blue-jeans high heels” to see Nina Simone’s performance:

Nina is singing Mississippi Goddam. Me and D we look at each other and nod.

Nina plays the piano a long time as if she forgets we are there. But we are.

Nina goes Holy roller African all in one wave of her hands ragtime to classical

and back again. We are in her groove our seats rocking with our bodies. Our

young female bodies, big Afros and big dreams. The balcony is a smoky black

sway. The orchestra white. Someone fidgets. Another one coughs. Nina stops.

Quiet. Her voice a swift typhoon. You could hear their hearts hesitate. Stop.

Nina chuckles then returns to her song. Mississippi Goddam. It’s different now.

Bruised. Me and D we look at each other and nod.

Reading those lines, I wondered if the fidgeting orchestra members were uneasy from the song itself or that they were the only white people, it seems, in the Harlem venue. In either context, the white band members’ tension is akin to that of the white folks who were in the movie theater watching Rosewood, a movie by John Singleton that told the story of an almost unknown incident in a small Florida town.

The false testimony of a white woman accusing a “black stranger” of raping her set off a mob of angry white folks who hunted down and lynched most of the black men in town. According to rumors, the movie caused such a stir that white folks, attempting to avoid any assumed confrontation afterwards, snuck out of the theater before the movie ended.

In me and Nina, Monica Hand doesn’t shy away from confronting sensitive topics. “In these poems she sings deep songs of violated intimacy and the hard work of repair,” Inaugural Poet Elizabeth Alexander writes of Hand’s book. Hand touches on that violated intimacy in the poem “Everything Must Change,” a poem in which Rufus, a boy from the neighborhood, invites Hand’s speaker to go see Nina Simone perform at the Blue Note.

As the poem goes, Rufus, who’s polite and respectful in front of Hand’s mother, turns out to be a jerk. Under the guise of going back to his parents’ spot to get some more money, Rufus lures Hand’s speaker into his basement bedroom. There:

he starts begging me to give him some—just a little he says. I’ve never done it before and/ I’m not scared just not really interested. I want to go. See Nina Simone. He / begs real hard. Even gets down on his knees like James Brown: Please, please,/ please. I give in. Stop his begging. It’s over. Quick. No big deal. I don’t feel a/ thing.

They never made it to the show. Part of repairing that hurt is not seeing Rufus anymore: “[…] when my mother asks what happened/ to him I just shrug my shoulders or tell her I think he’s dead. Just like, I tell the/ kids at school who ask where’s my daddy.”

In the poem “Daddy Bop”, Hand’s speaker gets herself into a mess of trouble trying to repair that hurt from her father. “Knew him like a fifth of vodka/ he tasted good with sugar and lime/–left me with the shakes/ so if you see me on the street/ acting like a bitch–/ I’m just missing my daddy,” according to Hand’s poem. “Lost all my self-respect/ in bed with some men some women/ who smelled like my daddy/ if they could love me, maybe he would too/ just understand everybody needs/ some respect he was my daddy”.

And just when things seem hopeless, Hand’s speaker turns to Nina Simone for answers through her six “dear Nina” poems and the section “Nina Looks Inside,” which sets itself apart from the rest of book with white text on black pages.

“These poems are unsentimental, bloodred, and positively true, note for note, like the singing of Nina Simone herself,” according to Elizabeth Alexander.

Poets Terrance Hayes and Tyehimba Jess also agree. “She [Monica Hand] shifts dynamically through voices and forms homemade, received and re-imagined to conjure the music (and Muses) of art and experience,” writes Hayes.

After reading me and Nina, I felt that Jess best summed up this collection. “Monica A. Hand sings us a crushed velvet requiem of Nina Simone.” Whoa! That’s the best way to put it. “She plumbs Nina’s mysterious bluesline while recounting the scars of her own overcoming,” Jess continued. “Hand joins the chorus of shouters like Patricia Smith and Wanda Coleman in this searchlight of a book, bearing her voice like a torch for all we’ve gained and lost in the heat of good song.”

I don’t think I could’ve said it any better.

Well Done. With Marian’s contralto embellished with a “few” ounces of sand. The ‘souls of black folk’ written across every emotional timbre expressed. Like her, I wish I knew what it was like to be FREE.

“D” /om

Thanks Omegetymon. I’ve never heard Nina Simone’s voice described that way, but it’s an amazing description (“Marian’s contralto embellished with a ‘few’ ounces of sand”). Thanks for reading!

I was a Stagehand for thirty years. My ‘Godfather’ is J.C. Davis 20 years as James Brown’s Music director. I’m that nobody that takes “note”.

Addendum: I ‘tried’ to be like Bobby McFerrin and study voice performance… with McHenry Boatwright, ( the man I saw SING at Kennedy’s innauguration.)

A thorough, in-depth review. This poet/performer is charming and deep in person, but she practically flies off the page in your review. You selected thematically, creating a slice of the poet’s life, not just her work. I was very lucky to read with this artist in Philadelphia.

Thanks for the encouraging words, Aquaverse! I really enjoyed Monica Hand’s book. I also consider myself lucky to know her. I’m glad you two connected in Philly. Please stop through the blog again!